from FIXED CYCLE

Most people and organizations plateau. They get good enough that consumers or audiences like what they produce. They develop a way of doing their jobs that becomes reflexive, so that it is hard to see outside of the established pattern. It feels comfortable and likely to achieve established goals. Unfamiliar alternatives at first feel clumsy and risky in comparison. They stick with what feels "right," which results in a slowing of growth and a loss of flexibility.

to DYNAMIC CYCLE

The alternative to a fixed cycle is to build an expectation of growth and methods for achieving it into the habitual patterns that shape how people do their jobs. A dynamic process depends on having (1) aspirational standards that continually remind us that more is possible, (2) methods for researching and experimenting with alternatives to reach closer to that possibility, and (3) methods of gathering and using feedback that provide a clear signal when we are and are not on track.

EXPERTISE

Extraordinary accomplishments, the ones that really inspire us, often seem out of reach. As a result, we make the easy mistake of attributing them to “genius,” as if it were a quality that belongs to another world. It is not. It develops through a process of growth and learning that we all can engage in. Whether it is Brunelleschi's dome in Florence, a breathtaking consumer product that people not only use but love, or the ability to facilitate social change in a group of people where others thought it was impossible, the final product looks magical; but the process of achieving it happens one very human step at a time.

Psychological research on expertise and expert performance emphasizes that some people find a path of growth that allows them to improve for many years, but most people and organizations plateau once they have reached adequate performance. Research in many fields, from financial analysis to some medical specialties, shows that dramatic under-performance is the acceptable norm. Even in the fields where it is hard to measure performance for research purposes, it does not take a lot of looking around to see a huge gap between exceptional performance in a rare few and the norm within the field. Think of entertainment, architecture/ construction, political leadership, and on and on. Achieving at the normal level can meet many of our emotional as well as professional needs, but it will not help shape a better world. It also will not be be as rewarding as making progress every day towards a vision that we love and that exceeds the normal grasp. All people and organizations are much more prone to sliding into a plateau than they realize. Cognitive biases, wired into the way that we think, tend to close off possibilities once we find a familiar and functional way of approaching a situation. Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls these "What You See Is All There Is" biases. The result is that we and our organizations can get stuck in the demands of our field and in our way of doing things and not really see any alternative.

The alternate path keeps us open to our potential impact and striving to reach it. It is based on a virtuous cycle of identifying standards beyond the norm and building motivation by seeing ourselves make steady progress towards them. The exceptional starts to seem possible. The work is to develop a practice, as an individual or within the culture of your organization, that includes the fundamentals that make that cycle possible.

PRACTICE WITH FEEDBACK

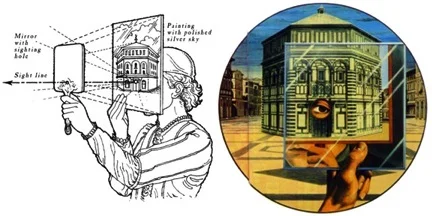

Brunelleschi developed mastery early in his career by comparing his work to the greatest human accomplishments and to nature itself. He discovered linear perspective, changing the world of painting forever, during this period. The discovery appears to have occurred by struggling with the discrepancies between his drawings and the image of the natural world striking his retinas. The illustration shows Brunelleschi comparing a reflection of a painting and a building in Florence by moving a mirror back and forth. In this way, he could see without moving his eyes when there was no difference in proportions between the two. The same information had been available to artists through time, but none of them used it systematically enough to be able to conform image to nature so successfully.

Anders Ericsson, one of the leading researchers on expertise, has emphasized the crucial importance of informative feedback guiding practice. Using concrete feedback challenges "what you see is all there is" biases, because you are specifically looking for the differences between what you achieve and a standard you are trying to grasp. With practice, you vastly extend your skills. Forcing ourselves to focus on the discrepancies between where we are now and an objective standard that we want to achieve keeps us in "beginner's mind," that stage when we have to think deliberately and creatively because our current way of doing things is not good enough.

The trick is finding ways of using feedback to help us achieve the goals we care most about. Practicing with feedback is standard in activities like athletics, but the areas of accomplishment most of us care about are more unique. We cannot just compare our performance to other athletes, because we are trying to accomplish something different. Nevertheless, finding relevant systems of feedback that challenge us and push us in the direction we want to go is at the heart of growth. Finding the right system of feedback has transformed medicine, created the scientific revolution, and resulted in the development of linear perspective. It can do the same for you and your organization.

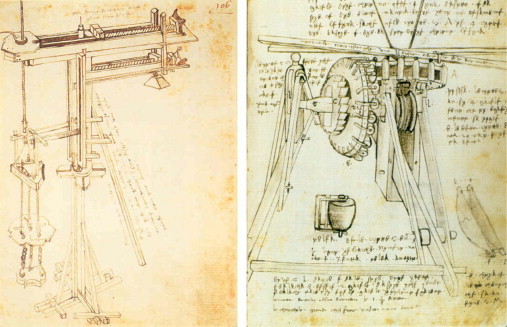

A hoist for lifting stones during the building of Brunelleschi's dome was more sophisticated than any hoist before it. Brunelleschi designed it because no existing hoist could manage the challenges of a dome of the scale he was building, a challenge he met and mastered rather than letting it deter him. The sketch is by Leonardo da Vinci during his apprenticeship. Leonardo's attention to detail shows his own meticulous effort to master the possibilities of human innovation.

GROWTH ORIENTATION AND GRIT

What qualities do we need to bring to the journey that will keep us engaged through setbacks? Carol Dweck is a psychologist with a tremendous research program showing that people who believe that they can improve with practice are, in fact, much more resilient in the face of setbacks. Psychologist Angela Duckworth has researched a complementary construct, which she calls grit. Grit includes determination in the face of obstacles, a steady willingness to stay on a path long enough to become deeply proficient, and a personal passion for the goal you are pursuing. She makes a compelling case that it is the strongest predictor of future performance, when measures of current ability and past achievement are taken into account.

Grit and a growth orientation can be learned. Developing beliefs in resilience and growth is fundamental to any individual or organization who will have the sustained motivation to stay on the hard path to exceptional innovation.

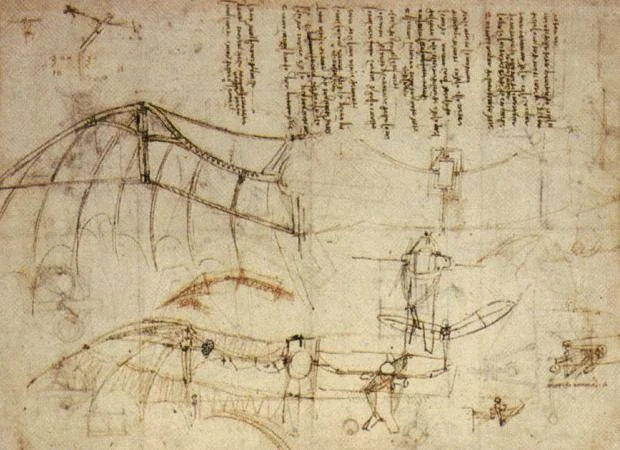

Sketch for a flying machine by Leonardo. He said, "When once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return."

THE HIGH BAR

Because we tend to stop learning when what we do now is good enough, it is vital to keep a clear, hungry focus on a standard that we have not reached and that we are hungry to achieve. It may be recognizing the enormous difference between a good product and one that is elegant enough to be a thing of beauty. It may be a conviction that technology at its best can feel like an extension of ourselves -- and that only the most extraordinary products will produce that effortless connection. It may even be an ideal that is never fully achieved, but it is a practical standard because it drives a person to try new things, to discover what works and what does not, and thus to make progress in the direction that inspires her. One of the most difficult issues for any group or organization is identifying "high bars" that are both motivating to the point of being a central driving force and practical in that there is a clear path for approaching them.

Many of Leonardo's sketches fascinate us because of the precision with which he studied the forms that elicit powerful emotions, with multiple perspectives resulting in slightly different effects.

PERSONAL JUDGMENT

If we are not trying to become an athlete, or a chess player, or any other activity where everyone is trying to achieve a common standard, our growth has to be guided by personal standards. To be able to identify high bars for those standards, we have to be good at knowing what most inspires us. In addition, in order to move towards those high bars, we have to have a clear signal when we are on the right track and when we are not. Part of that will come from feedback from others who understand what it is we are trying to build. But the work ultimately has to meet a benchmark within ourselves. The mind creating the product is the one that has to be able to discriminate what is great from what is not quite so great. Like all skills, making that discrimination requires training. For example, we can repeatedly look at the range of work existing in our field, examine the fine differences in reactions that lead us to embrace one over another, and study what it is that makes us prefer it. Over time, we improve our judgment -- the ability to use our gut to select what feels most exceptional to us. Our gut then gives us well-trained intuitions when we are on the right track. As we develop judgment and build the confidence to use it as a central guide for our work, we begin to trust ourselves enough to take unconventional paths. We can be bolder in orienting our work towards what is most inspiring on a personal level. After all, others will not be inspired by work that did not inspire its builders. A world in which more work is built by people and teams who have put their heart into what they create is a world that will inspire all of us more. It is a world where humanity is the heart of excellence.